Against Stoke, we concentrated on how Liverpool played in possession. Here again, for different reasons, we will do the same, focusing less on the execution of Liverpool’s attacking game plan and more on the implementation of their shape when on the offensive.

Line up

Rodgers opted for the same team that had started against Stoke. At this early stage of the season, where performances are often not at their most fluent and coherent, it’s generally important to keep some type of stability of selection and although there were two or three changes Rodgers could and arguably should have made, he made the decision to stick with the same eleven he had chosen previously.

What was different was the arrangement of these players, particularly in possession. We’ll come onto this more in a second.

The most basic changes Rodgers made were:

- a) switching Ibe to the left flank.

- b) moving Coutinho across to the right (although with a very different role in possession).

- c) bringing Lallana inside to play more or less as a central midfielder.

Why he did this became more obvious as the first half wore on.

Analysis

It’s often said that formations are neutral. In many ways that is true. A formation does not dictate your style. It does not dictate how attacking or defensive you will be. It does not necessarily dictate which areas you will be strong in. It does not dictate whether you will press or sit off. It does not dictate whether you will be overrun in midfield. It does not dictate whether you will get enough bodies forward.

Indeed part of the reason for the problem of defining tactical analysis by formation match ups is that in-game, a team very rarely holds the direct formation they are playing on paper. This is especially true in possession, where shape is less important than it is when a team is defending. Little movements and positional adjustments change a team’s shape almost every second of play. It is not at all uncommon for teams to defend and attack in two extremely contrasting formations. Interestingly enough, despite many thinking Rodgers first decided to switch to three at the back last season in December, he actually tried it out a month earlier in the 1-0 loss away to Newcastle – a game where Liverpool played a very definite 4-2-3-1 when defending, merging into a clear 3-4-2-1 when attacking.

In this game, Rodgers tried something similar. When the team dropped back into a block, they generally played, strictly speaking, something between a 4-1-4-1 and a 4-5-1. Henderson swept up just behind Lallana and Milner in central midfield. Ibe fell back on the left. Coutinho did a similar thing on the right, though was often covered by James Milner, allowing the Brazilian to stay higher up the pitch to dictate counter attacks when possession was regained.

When Liverpool had the ball though, they played a very different shape.

Part of the criticism of the performance against Stoke was formed by how poorly Liverpool spaced the pitch. This is one of the basic rules of football – when you have the ball you make the pitch big, when you don’t you make it small. That doesn’t mean there can’t be asymmetries or any lopsidedness at all. It’s just that one of the principles of good defending is to make play predictable by forcing the opponent to have to attack one area or side of the pitch. If the attacking team itself neglects to use or even position any player on one side of the pitch when attacking then that generally makes it easier for their opponent to concentrate resources on their strong areas without having to worry about being opened up elsewhere.

Against Stoke, Liverpool had a problem with their left hand side. Lallana, playing at LW, pinched in very narrow when Liverpool had the ball, whilst Joe Gomez never got high up the pitch and often turned inside on his right foot when he received possession, cutting off the line of pass down that flank anyway. This meant that Liverpool were extremely right-centric, using the right flank for 51% of their time in possession, a rather alarming figure considering they weren’t getting much joy there anyway.

In this match however, Rodgers spaced the pitch in an interesting and more balanced way.

The first way he did this was by moving Ibe across to the left hand side. This meant that Liverpool now had a player who would be comfortable pulling wide of the opposition’s block on that flank, stretching the play. Against Stoke, Liverpool didn’t have this player on the left; Lallana kept cutting inside without overlaps from Gomez, whilst on the other side Ibe ended up, to some extent, restricting Clyne’s attacking enthusiasm.

In this game though, Clyne now had the space to push up high on the right, whilst on the left Gomez was able to stay deep without the responsibility of having to spread the width because of Ibe’s positioning in front of him.

The second thing Rodgers did was to ask Coutinho to move inside just off Benteke when Liverpool had possession. As Liverpool’s most penetrative and creative player, Liverpool needed his influence in a midfield otherwise made up of three more functional, energetic players who perhaps lack the creativity and the ability to dictate attacks around the final third. Coutinho, moving inside from the right, would be able to offer the quality that the others couldn’t.

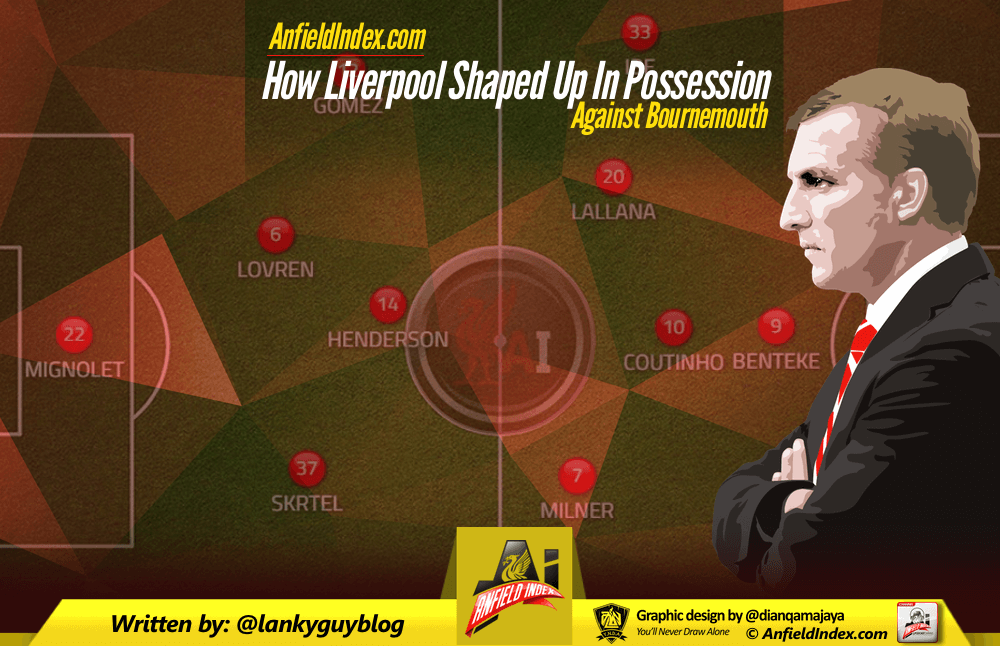

All this meant that in possession, Liverpool were effectively set up in something close to a 3-1-4-1-1. Gomez stayed back along the same line as Lovren and Skrtel. Henderson acted as the pivot in midfield, dropping deep to get the ball, often between Lovren and Skrtel. Ibe and Clyne were wide on the flanks helping to stretch the play, with Milner and Lallana both pushing up from CM and Coutinho effectively acting as the no.10, with freedom to join Benteke or to drop off deep to get the ball in central midfield.

Whilst Bournemouth started the game well, with good energy and enthusiasm, this setup dampened their attack more and more. As Liverpool grew into the game, Bournemouth lost their offensive threat, in part down to how Liverpool shaped and spaced themselves in possession – two players on the flanks, stretching the pitch, numerical superiority in the middle with effectively four midfielders, plus good cover at the back with Gomez’s deep positioning alongside the two centre-backs. This made it difficult for Bournemouth to hurt Liverpool immediately on the transition, especially with Liverpool’s counter-pressing once they lost the ball.

In the picture above, we see a good example of this setup being described. Clyne is on the ball, having got forward on the right. Gradel has dropped back to mark him. Milner and Lallana have pushed up in the middle, leaving Coutinho freer on the top left of the screen, having dropped off in front of the Bournemouth midfield.

As Clyne looks for a pass, Henderson makes a run forward to take his marker away, opening up the passing lane to Coutinho.

As Coutinho picks the ball up in midfield with no pressure, there are a couple of things to take notice of. First of all, we can see Gomez’s reserved positioning on the top left of the shot. This was why Liverpool were functionally playing a back three for the majority of the time in possession, even if it was lopsided towards the left.

Further forward we can see Ibe in a lot of space on the left flank. Matt Ritchie has had to pinch in from the right in order to support Bournemouth’s two CMs in dealing with Liverpool’s numerical superiority in the centre. This has left Liverpool’s most direct dribbler in a lot of space on the left flank, either to act as a decoy to open up room inside or to take on the full back if the ball is switched quickly.

This is how Liverpool spaced the pitch more effectively than they did against Stoke. Gradel was generally forced to mark Clyne moving forward from right-back, leaving O’Kane and Surman to try and control Lallana, Milner and Coutinho in the middle. If Ritchie and Francis on the right tucked in to support then Ibe was left with more space wide on the left to receive the ball and cause damage.

One of the interesting, if more subtle, things to notice about this is how aggressive Liverpool’s positional play in midfield was. Let’s go back to the first shot we saw.

Notice as Clyne receives the ball how high up Milner and Lallana are. In possession-based sides, generally much of the focus is on retaining depth and options behind the ball. In midfield, players position themselves in order to make themselves available for the pass, if not the immediate one, then the next one. Of course there also has to be depth ahead of the ball otherwise it’s too easy for the opponent to condense play into the middle of the pitch but despite this, much of the positional play is generally founded on being in the best positions to give the ball carrier easy options in possession and having superiority in deep and central midfield.

In this match though, Liverpool had relatively little focus on indirect, domination of possession in the centre. The positioning was more based around pushing Bournemouth’s midfield back and freeing Coutinho to create something in the final third. The movements were fairly simple – Henderson played as the pivot in midfield, starting moves from deep, while one midfielder, generally Milner or Coutinho, would drop off to receive, with the other two of this temporary midfield four generally pushed up between the lines.

One of the biggest effects this had was to push Bournemouth deeper than they wanted to go – despite their energy and intent not to allow Liverpool to control the game, their midfield often ended up falling back too far, with two or three Liverpool players between the lines, plus Benteke dropping off. This, combined with Liverpool’s coverage in pressing, made it difficult for Eddie Howe’s side to apply concerted pressure consistently throughout the match.

It has to be said Liverpool didn’t play well – this was not a dominant performance by any means. Despite having more of the ball, they didn’t particularly exert match control through retaining possession and circulating through midfield. They didn’t keep probing for gaps. They didn’t move the ball around waiting for Bournemouth to make a mistake. In fact they didn’t really create very much at all. As has often been the case this calendar year, a large amount of the creative responsibility fell on Coutinho – indeed, more than once in the match, a Liverpool player made a three or four yard pass to him just to get him on the ball. With Lallana anonymous for large parts and Milner not offering anything special, Coutinho was often the one asked to manufacture something in the final third – to beat a player, to play a penetrative pass behind, to have a shot on goal. Whilst his quality was obvious and whilst he performed better than he had against Stoke, the same rustiness was also present and he missed a couple of good opportunities to give Liverpool a comfortable lead. The team’s other main attacking threats, Ibe and Benteke, both had decent games, particularly the latter, but as against Stoke, the cohesion in attack wasn’t especially impressive and Liverpool lacked the fluidity that has marked their best attacking performances in the three years under Rodgers.

Conclusion

The new setup though was definitely an improvement, especially in regards to how Liverpool spaced the pitch. Whether Rodgers will use this idea in possession again is unclear; given his flexibility with formations, it would be a little unwise to predict that he’ll start using any particular shape on a consistent basis, whatever it is. It could be that this lasts for just one match. With Moreno getting sharper, it’s very possible that he will replace Gomez at left-back at some point within the next few weeks and effectively rule out this exact setup. With increased cohesion and sharpness though, as well as the inclusion of Firmino and Can, this is an interesting option to have. Given Rodgers’ like for a back three in possession, it’s a possibility, even if he retains the back four at base.

We’ll just have to wait and see what he has planned for the next match against Arsenal.