Any back-line – let alone the back-five of Liverpool’s – will face adversities in the form of the high initial press in trying to lay the foundation for attacks. Jürgen Klopp’s system for Liverpool works in a multitude of ways in order to overcome these adversities as mentioned in Part 1 here, but nevertheless, football is still a team game.

It goes without saying that the five players in the aforementioned positions – both centre-backs, the full-backs, as well as the deep-lying midfielder who drops deeper – face a multitude of risks when trying to advance possession from the defensive-third into midfield areas. From high-presses to inherent risks in certain areas the pitch (as well as the severity of individual errors should they occur), there are instances where the back-five cannot uphold the burden alone.

This is where the midfielders come into play. By default, midfielders are seen as players who are responsible for matters at both ends of the pitch. Though in terms of building up play, they are the players who link the defence to the forwards, in simplistic terms.

Adding a Layer above the Back-Three

As mentioned in the first part of the article, the back-three often suffers from teams who press high up the pitch; teams who are willing to push players up and rely on the pace of their own midfielders to drop back quickly to defend in transition. If 3 players are deployed to chase down each player in the back-three for example, it could spell trouble for Liverpool.

This means that unless the back-line of Liverpool’s can consistently beat their marker and drive up the pitch with the ball at their feet, passes between them will more likely be lateral ones from one side of the pitch to another. This delays build-up play, meaning that even if opposing teams give in to the slower build-up and drop back to defend, there will still be at least 10 men behind the ball, which makes it difficult for Liverpool to get into good positions in the final third. Moreover, losing the ball while trying to get the ball up-field by attempting to dribble past opposing markers will put Liverpool in a horrible spot.

Also mentioned earlier was the full-backs who could be a way out for the back-three both on and off the ball, making the 3 forwards in an assumed 4-3-3 formation make a decision on how they structure themselves during the high-press, almost all of which seems unfavourable for them. The problem increases significantly, however, when opposing teams send a flock of players up the pitch to press. This is when full-backs don’t always become the best outlet for the back-three.

By virtue of their position and the area covered, the risks that full-backs face due to their game being played primarily near the sidelines, midfielders do not. “Winning the midfield battle” is not simply a phrase being thrown around for kicks and giggles simply because the zones covered by the midfield areas can dictate which team will be in control. Even without having the ball, a good midfield who is able to nullify another midfield from consistently advancing play up the pitch can be seen as the more successful team.

For Jürgen Klopp’s Liverpool, the two midfielders who play in more advanced positions compared to Jordan Henderson have rotated between three players for the most part – Georginio Wijnaldum, Emre Can, and Adam Lallana. The different combinations of the above results in different roles being carried out by each of them, but the underlying objectives still remain.

With that said, while Liverpool appear to be losing a man in midfield after Jordan Henderson drops to join the back-line, it doesn’t mean that they lose midfield control because the buck doesn’t stop there. To build on the numerical advantage, we often see one of the two midfielders dropping to create a back-four once again, this time with two centre-backs and two midfielders – all of whom have some ability to get the ball into midfield areas.

This is usually done when the full-backs are in higher areas of the pitch, whereby the back-three might require help from midfielders by getting them to receive the ball deeper down the pitch. Essentially, the three-at-the-back formation can easily shapeshift to become a 2-2, with Jordan Henderson stepping up slightly and the “deeper central midfielder” dropping to either side to form a double-pivot. This makes it difficult for opposing strikers to press as they cannot pose as a threat by simply running in a straight line horizontally across the pitch as, say, in a flat back-four.

Versus Stoke: The example above highlights the first scenario whereby we see Georginio Wijnaldum who looks to stay on the same line as Jordan Henderson to form a double-pivot, with the latter stepping up from the centre-back line. Also note how far up James Milner has pushed up but essentially, the structure above makes it more difficult for all three of Stoke’s players to press the back-line.

Versus Bournemouth: The second scenario would be when the full-backs have pushed much higher than the midfield line and instead of converging in the middle to form a double-pivot, the “deeper central midfielder” drags wide and occupies the vacated full-back spot instead. This forces opposing teams to decide if their winger/wide player should track Liverpool’s midfielder’s movement to the full-back spot or if a midfielder of their own should do so.

Uncoordinated teams will struggle coping with the required adaptation and will thus have their pressing structures disrupted. Otherwise, coordinated teams will have to weigh the pros and cons from either of their decisions – deploying a winger would mean possible overloads towards their own full-backs should Liverpool advance play quickly, while deploying a midfielder would mean exposing the central areas of midfield.

The other midfielder, who shall henceforth be referred to as the “advanced midfielder”, acts as the link-up player between the defence and the attacking midfielders and is tasked with making delayed drops into deeper areas of the pitch, typically assumed by Adam Lallana and sometimes, Georginio Wijnaldum. This also entails a ‘2-1’ midfield structure rather than the ‘1-2’ structure on paper.

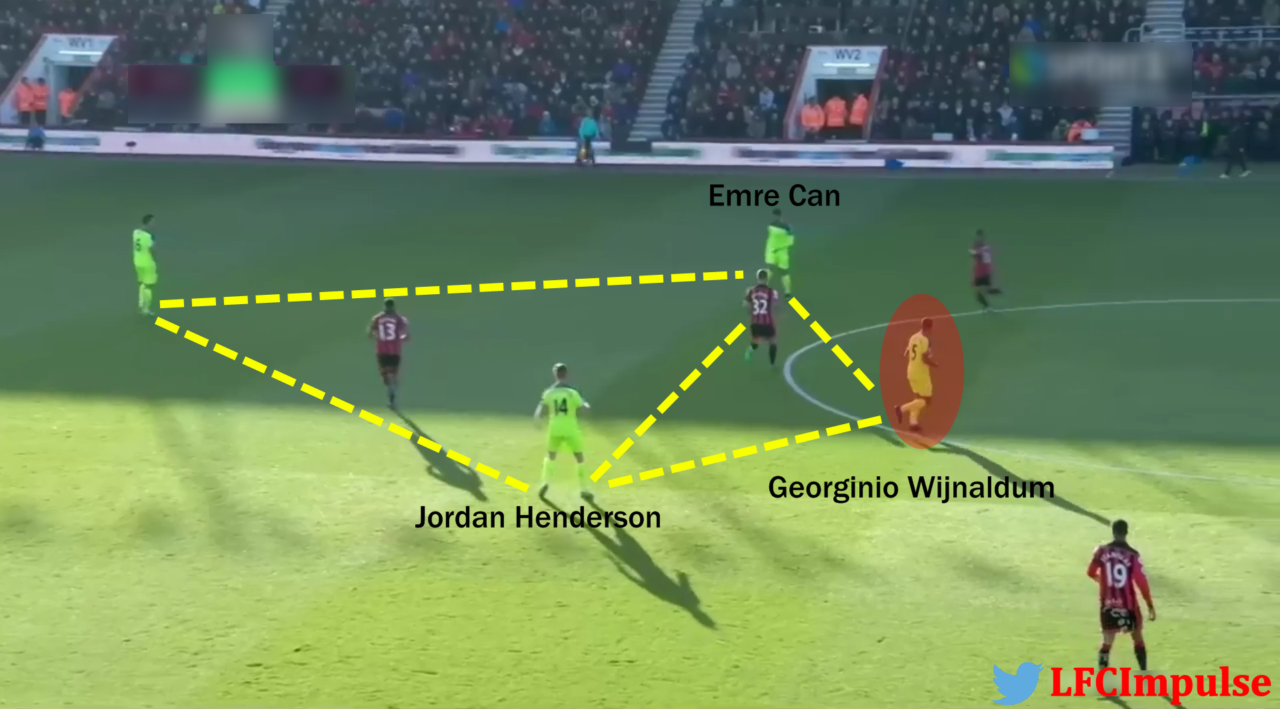

Versus Bournemouth: An example of the ‘2-1’ structure as seen above, with two passing triangles formed when the centre-back is included. The objective is to allow the ball to be built-up by the centre-back and midfielder pairings first before adding another man in build-up play. If they were to make earlier runs down the pitch and an opposing midfielder tracks this link-up player, that would mean that an additional opposing player is present to press the players involved in the initial build-up. Here, because Wijnaldum is already out of the view of the three Bournemouth players, should a pass be made to him, three of them will essentially be taken out of the game at least momentarily.

Versus Stoke: Another ‘2-1’ midfield set-up, with Adam Lallana being the ‘advanced midfielder’ who is able to choose when, if at all, to drop deeper down the pitch closer to Jordan Henderson to assist in build-up play.

In short, this link-up player would make delayed runs down the pitch instead. This achieves multiple things – the first being that if both of these advanced midfielders drop simultaneously, it becomes easier for opposing midfielders to track the movement as well (when one drops, the other will as well). The next would be to confuse players who are in the midst of pressing the players deeper down the pitch.

Say the first midfielder drops and already attracts another opposing player to press him. When the second midfielder drops but at a later time, it means that rotating players around to cover becomes even more difficult. As mentioned earlier, when the timing of the drop is delayed, it becomes less predictable for the opposition to know when to track a player and/or when to rotate player around to sufficiently mark each of Liverpool’s players.

Completing Passing Triangles out Wide

A consistent trend in Liverpool’s play has been how the players operate in wide areas. Gone are the days of the traditional set-up whereby wingers look to take on his respective defender 1-on-1 while the corresponding full-back or wing-back overlaps to confuse defenders or force errors during the rotation of marking before ultimately putting a cross into the box.

With the increased emphasis on utilising the wide areas without an over-reliance on crosses by Jürgen Klopp, passing triangles being formed in wide areas have become a common theme. As this section covers only the midfielders’ role in these triangles, the functions of the full-backs and the wide players will be referenced in a smaller scale.

The most obvious case of Liverpool’s midfielders being involved in passing triangles in wide areas are on Liverpool’s right flank, with Adam Lallana often being the midfielder who pushes wide to support Sadio Mane and Nathaniel Clyne.

Versus Sunderland: Often sticking to the half-space just outside the box, the advanced midfielder, i.e. Adam Lallana, will be looking to receive the infield pass from either of the aforementioned wide players and subsequently try to play the through-ball infield to link-up play. Ultimately, the objective here is to get either Mane or Clyne into an advantageous position in the half-space inside the box.

On the left flank, these passing triangles also exist but to serve a different purpose simply because of Philippe Coutinho’s tendencies when he plays on the left by playing much more narrow than a typical left-sided winger or forward would. This movement infield vacates space on the left side of attack for other teammates to occupy. Once again, as this part focuses on midfielders, the role of the left-back specifically will be covered in a later piece. With that said, the midfielder tasked with supporting play on the left flank has two options on the whole: to either be slightly conservative as the left-back drives into the vacated space, or to take up the vacated space himself.

An example of a more conservative take on the role would be what Georginio Wijnaldum does. As a player who isn’t blessed with pace, a more conservative role suits him far better. When Philippe Coutinho cuts infield and when James Milner bombs down the left-flank, he opts to stick closer to the corner just outside the box. This allows him to do two things for the most part.

Firstly, he can still be the link between the left-sided full-back and the left-sided attacking midfielder who has cut infield, similar to what occurs on the right side with Adam Lallana. However, the onus of putting players in the position to utilise the half-space on the left side is not being placed on someone like Georginio Wijnaldum too much, given how great a player Philippe Coutinho is in doing so. Secondly, with the left-sided full-back pushing up nearing the byline, the midfielder is ready to drop back in the event that the ball is lost and the opposing teams breaks on the counter.

The second option is for the midfielder on the left side to drive into the void left on the left flank himself, or at least put himself in a position to do so. Emre Can has a higher tendency of doing this due to his dribbling ability.

Versus Crystal Palace (1): Here, Emre Can begins to pull wide as Alberto Moreno occupies the half-space, both of which occurs after Philippe Coutinho has already drifted infield.

Versus Crystal Palace (2): Philippe Coutinho and Emre Can have essentially swapped positions. While Emre Can isn’t expected to deliver the pinpoint cross, the movement out wide allows him to be a free man which opposing defenders have to be wary of.

Should one of their players opt to charge out to close him down when he goes on the ball, it puts Can in an advantageous position given that he just has to read the defender’s direction and push the ball away from him to beat his man. This also forces defensive structures to move and adapt when the defender charges out to close a free Emre Can down.

The varying roles of the two advanced midfielders ahead of Jordan Henderson provides for a higher level of flexibility in terms of adapting to the different situations. This is also why a player like Georginio Wijnaldum is a vital asset to Jurgen Klopp’s Liverpool side given how flexible he is to be able to suit different positions and for tactical reasons as well. This can be said about other midfielders who have played too, albeit to different extents.

When build-up play appears to be stagnant, either midfielder can drop to form a double-pivot with Jordan Henderson or to drop to either side of the full-back to form a flat-four, pushing more naturally-wide players higher up the pitch. When the opposition deploy overloads high up the pitch in wide areas, either of the two midfielders can drift out to create the passing triangles necessary to overcome this.

Needless to say, in terms of build-up play, the back-three are assisted by both the full-backs and the midfielders available. However, with inherent limitations and a higher degree of predictability, full-backs can only do so much. This is where the midfield function comes into play to ease the pressure of high presses or targeted isolations from opposing teams. With possession successfully built up, the next sequence of play would be to attack, attack, and attack!