A manager requires perpetual change if he’s to succeed in the savage land that is the Premier League.

That’s the narrative that gets swung about on the regular, amidst pundits and fans alike. In Pep Guardiola’s first season, his tactical ministrations were seen as too imposing, not giving English Football’s top tier its due. Jose Mourinho has been accused of remaining “stuck in his ways” on multiple occasions; accusations which surprisingly were most stark in the Champions League against Sevilla. Even Jürgen Klopp, whose Liverpool team has only improved under his tenure, is often called in for criticism of stubbornness, and a “lack of plan B”.

But is it something of a fallacy? Just this season, Klopp played a back three with two central midfielders (against Brighton), multiple variations of his acclaimed 4-3-3 (varying the midfield setups) and even returned to his Dortmund side’s 4-2-3-1 in the final game of the season (also against Brighton) to deliver a typhoon of attacking football.

So too did Klopp tweak in the 4-1 victory against West Ham, when supporters got a peek into a potential future: the 4-2-2-2.

History Repeats

It should be noted, that this isn’t something the German has simply pulled out of the blue, off on a fanciful tactical escapade derived from a dream he might’ve had about gegenpressing. Does Klopp dream about gegenpressing? Probably not.

At Dortmund, when confronted with the dilemma of making a strike force of Robert Lewandowski and Lucas Barrios function in tandem, he opted to switch from a 4-3-3, which has the Pole drifting in from the right and instead made him one of the focal points. With Shinji Kagawa and Mario Götze hovering around them like buzzards, and the midfield condensed enough to both protect the back four and allow the fullbacks to bomb forward, it would become the 4-4-2 diamond formation, and ultimately the 4-2-3-1 that saw Dortmund win consecutive Bundesliga titles.

In the 4-1 victory against West Ham, Klopp’s adherence to Arrigo Sacchi’s philosophy that “formations are a myth” seemed quite clear: the team seemed to play 3-5-2, 4-2-3-1, and a 4-2-4 during the first half. All of it, however, was oriented from the core foundations of two midfielders, two wingers, and two forwards; one of which roams about doing whatever he pleases (a part Roberto Firmino was born to play.)

It wasn’t just a one-off, either: Sam McGuire wrote a detailed piece on why Klopp’s new system was a long time coming for This is Anfield back in November.

The Tactical Tweaks – Dominating the Transition

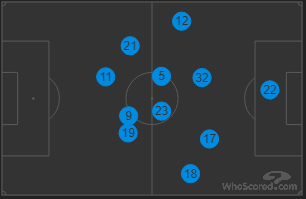

A quick peek at the average positions chart from the victory against West Ham shows exactly why Klopp favoured the 4-2-2-2; it gave the other team the space to push slightly higher, whilst restricting the positions they could play in.

A lack of a third man in midfield would invite West Ham to push up through the middle, helped by the high pressure of the fullbacks forcing them inside. That’s where the German’s team was waiting with a trap: midfielders ingrained with an instinct to harass in the right spaces, wingers coming back on the middle of the park to assist, and a lightning-fast Mohamed Salah to receive the first pass and engage the counter-attack.

Alex Oxlade-Chamberlain’s speed and dribbling ability was imperative, acting as the conduit between the midfield and front four, and allowing Salah to play as the auxiliary number nine. Klopp himself described it as a 4-4-2, which showed the roles Oxlade-Chamberlain and Mané played: as a hybrid of wingers and wide midfielders. Klopp’s justification for the tactic was more than simply funnelling a fluid attack, remarking that the change improved the defence. But, as Anfield Index’s Under Pressure podcast revealed on the post-West Ham edition of the podcast, the formation brought the press back with a blitz.

It makes sense, too. As Ted Knutson explores in his piece “Let’s Talk About the Press Baybee” (which will be referenced again in the coming words) pressing teams are all about winning the ball back in the most opportune moments for their own possession: essentially, winning the ball back with three players already bursting forward will lead to a better chance than winning it back while the opposition already has seven players in their own box.

The more compact 2-2-2 shape meant that Firmino’s manic off-the-ball work always had its supporting actor: Mané’s position, the closeness of the midfield two and Oxlade-Chamberlain’s relentless running meant Liverpool had more chances to press, AND more forward players when they did win the ball back.

It set up a blueprint for the way forward.

Buying to fit

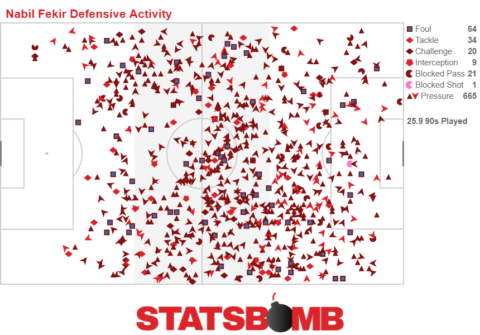

Anyone following Ligue 1 recently will have noticed Nabil Fekir’s immense goalscoring ability, as well as his versatility: he’s been deployed up front, in the number ten slot and out wide during his tenure at Lyon. However, what you might not have noticed is how relentless the man is at winning the ball back.

He’s dropped deeper significantly more often this season, with more attacking options at his disposal (often a hybrid of a midfielder and forward, rather than out-and-out shadow striker.) As Ted Knutson explores in his aforementioned piece, his pressing numbers aren’t dissimilar to Roberto Firmino’s: and that is rather incredible.

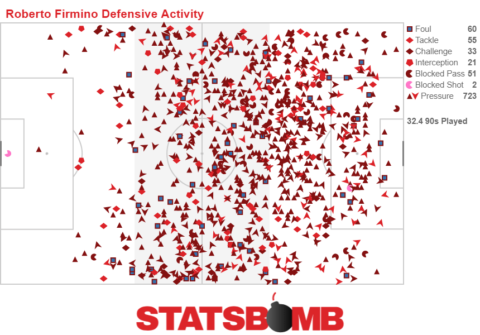

He has some work to do to match Firmino’s combined 77 tackles and interceptions, but then Fekir doesn’t work with the renowned pressing aficionado that is Jürgen Klopp, does he? Not yet, anyway.

There’s also the fact that passing through the middle will be encouraged by the proactiveness of Virgil van Dijk, not to mention the midfield itself, which is getting a revamp.

Fabinho and Naby Keita are very different players who, when put together, will create a superb partnership on paper. Yet they share one thing in common: they’re coming from sides who play variations on the 4-2-2-2.

Leipzig under Ralph Hasenhüttl were a press-heavy team that played in the fashion of their Director of Football: Ralf Rangnick, Narrow, quick and always seeking to win the ball back in as high up the pitch as possible, it’s a variation on Rangnick’s core ideal, one which Klopp shares.

Liverpool’s new Brazilian meanwhile won Ligue 1 in a swathe of counter-attacking fury and devastating transitions, as Leonardo Jardim’s 4-4-2 utilised the speed of their attacking players, quick delivery from deep and compactness of the system to sweep through teams. In the middle of it all was Fabinho: not so much an orchestrator as an organiser, ensuring everything was kept in line, in the knowledge that one falter would bring down the system.

Put them together, add in a little bit of intense French flair, and Klopp could well be planning to return to the 4-2-2-2 system next season. Given what Klopp’s adaptations have led to up to now, it could be quite something.