Despite dominating the ball and creating the lion’s share of the chances, Liverpool succumbed to a 3-2 defeat in front of their home fans as Diego Simeone’s Atleti survived the bombardment to score three goals in added time. Simeone’s side showed the catenaccio and Bilardisme mentality that has made them one of the most respected teams in Europe. Nonetheless, Liverpool were able to open up cracks in Simeone’s disciplined set-up to create chances that could have won the game. Liverpool’s performance was widely praised, whilst Simeone’s was criticised as anti-football, but both teams deserve credit for their tactical and technical displays in testing circumstances. This tactical analysis will identify Liverpool’s approach to attacking Atleti’s set-up, as well as identifying how Atleti’s set-up limited Liverpool’s danger men.

Atleti’s intent

Simeone’s compact 4-4-2 shape is designed to limit the opponents’ access to the middle of the field, particularly in front of the goal. When used effectively, this forces their opponents to progress the ball in wider parts of the field, thus forcing them to either cross (thus creating lower percentage chances) or take long shots (again these are lower percentage chances). Against Liverpool, the approach was no different and whilst Liverpool are renowned for being a side that creates chances from wide areas, Simeone’s approach was still effective in reducing the quality of Liverpool’s chances and limiting the threat of their most dangerous players.

Liverpool’s deep build-up play

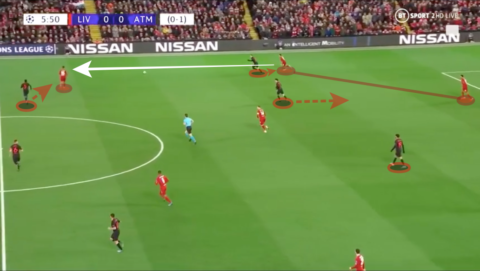

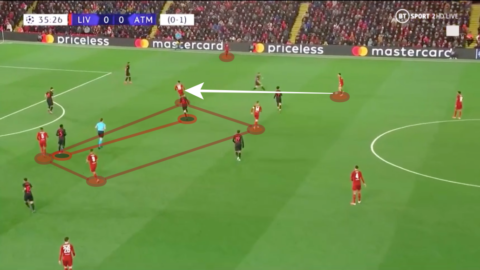

For most of the match, Liverpool had Atleti’s number when building up from deep. Liverpool tended to build up with 3 players in deep positions, designed to outflank Atleti’s 2-man strikeforce.

This often had the desired effect of enabling Liverpool to bypass Atlético’s high press. They were particularly effective in doing so when Alexander-Arnold dropped back into the back-line, due to his brilliant passing range. This allowed Oxlade-Chamberlain and Salah to occupy the right side of the field. Oxlade-Chamberlain was often able to run off Thomas Partey, who simply had too much space to cover once Koke moved to press Liverpool’s right-back. By moving in synchronisation, Oxlade-Chamberlain and Salah often opened up Atleti down their right side with Alexander-Arnold operating as a pseudo-quarterback in many ways.

However, Simeone’s second-half tweaks made his side somewhat less vulnerable to this approach. His wide-midfielders and strikers were less aggressive, with Marcos Llorente in particular more passive than Angel Correa when he came on. This tempted Liverpool to attempt to build-up with a 2-man back line.

Atleti responded by allowing Liverpool to pass to Henderson before pressing him aggressively if he received facing his own goal. This impacted Liverpool’s build-up from deep with Henderson uncomfortable receving under pressure from behind and showing less ambition as a passer than we have seen in recent weeks when given time. For a period in the second half, Atleti stymied Liverpool’s offensive threat.

Nevertheless, Roberto Firmino’s extra time goal came when Liverpool reverted to Alexander-Arnold playing from depth, with Gini Wijnaldum running off Saul before beating Lodi & crossing perfectly to Firmino.

Liverpool’s primary attacking threat

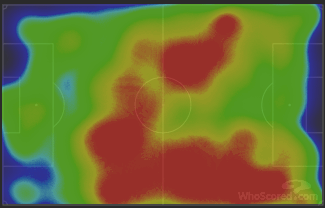

In much the same vein as their deep build-up, Liverpool’s primary route of progressing the ball into the final third and creating chances was in overloading Atleti’s midfield duo and attaining positional superiority against them by forcing them to have to cover large areas of the field. This generally manifested itself in Liverpool’s overwhelming use of the half-spaces and intricate combination play between the full-back, the near side number 8 and the near side winger.

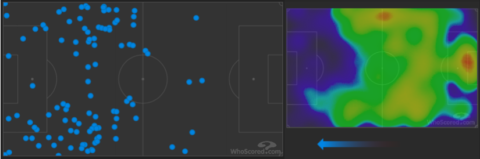

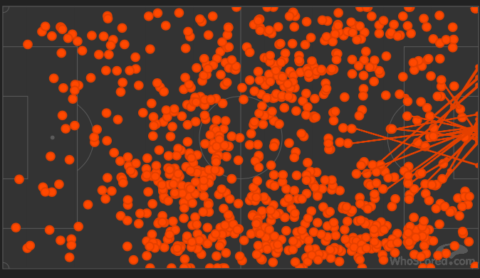

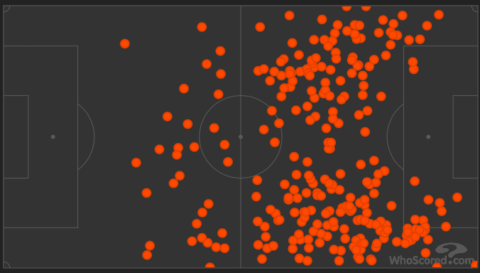

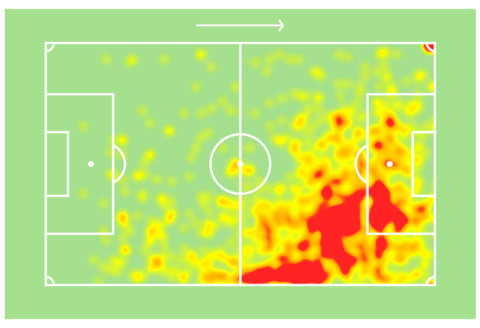

Liverpool’s heat map, touch map & the origins of their passes to the final third all reveal their focus on attacking through the half-spaces, whilst also showing their lack of access to the space immediately in front of the penalty area. Furthermore they also show the team’s focus down their right flank.

The incisive combination play utilised the passing quality of Alexander-Arnold (as well as Salah) along with the mobility and positional intelligence of Salah and Oxlade-Chamberlain. Despite rarely having clear numerical overloads on the right flank, Liverpool had the positional superiority as well as athletic superiority to routinely carve out good openings on their right side. The trio maintained their width well to ensure they could exploit openings when the ball was passed quickly from left to right. Wijnaldum’s first half goal was a product of such combination play. Most of Liverpool’s best attacking moments were products of these combinations.

Meanwhile, Liverpool adopted a slightly different strategy on their left flank. When the ball was moved out to Andy Robertson, Wijnaldum regularly made a run from inside to out whilst Roberto Firmino dropped towards the ball. This often created space for Firmino. The ball-far centre midfielder was rarely in position to impact play given his occuaption with Oxlade-Chamberlain; Liverpool were numerically superior. However, Robertson tended to lack the intent to fizz the ball into the dropping number 9. As such, this well drawn-up plan often went unrewarded.

Simeone’s masterclass?

There can be little doubt that Liverpool’s attacking plan was an effective one to create attacking openings against Simeone’s set-up. Jürgen Klopp and his staff deserve credit for the way in which they exploited or sought to exploit Atleti’s double pivot in particular.

However, when playing Liverpool, a manager must attempt to limit the threat of their most dangerous attackers – Sadio Mané and Salah. Simeone’s system forced Liverpool into tactical tweaks that caused Salah and Mané to adopt positions more akin to conventional wingers, rather than the inside forwards they tend to be. This reduced their threat and forced Liverpool to look to Firmino and their 8s as their primary goal threats – often in the air. That is a win for the opponent.

Furthermore, even though Liverpool had a high volume of shots, very few of those shots were high quality chances. There were often numerous bodies in the way, the attacker was attempting an overhead kick or they were headed chances under immense pressure. A high volume of low quality chances is not a great way to win a football match, especially against a goalkeeper as gifted as Jan Oblak.

Whilst Liverpool’s combination play created good attacking platforms and openings, Liverpool’s actual chances were not especially good. Combined with the fact that Liverpool’s most lethal attackers, Mané and Salah, were forced into wide areas, Liverpool’s chances of scoring decreased further. If not a masterclass from Simeone, Atleti’s tactics still had the effect of limiting Liverpool’s attacking threat.

Takeaways

Liverpool’s build-up and some of their final third play deserves significant credit. The toothlessness shown in recent weeks was replaced by incision and co-ordination as Liverpool repeatedly carved Atleti open down their right hand side to establish good attacking platforms. Alexander-Arnold, Oxlade-Chamberlain and Salah dovetailed particularly well. Liverpool needed more from Robertson and Henderson as penetrators however.

Meanwhile, Simeone’s tactics also deserve credit for forcing the likes of Salah and Mané wide and into positions where they could not hurt his team. Although Liverpool are effective at creating chances from wide positions, the number of bodies Atletico were able to commit to defending crosses and the profile of the Liverpool players attacking them ensured Simeone would have been confident of limiting Liverpool’s attacking threat from such actions. If not a masterclass from Simeone, it was nonetheless a good lesson in limiting shot quality and playing to your own side’s strengths whilst limiting some of your opponent’s. In football, you can certainly make your own luck.