Liverpool’s defensive line only seems to be put under the microscope after multiple goals are conceded in a single game. It’s an easy target for over the top, reactionary analysis. There was no real mention of it last season when the Reds conceded 17 goals in 27 Premier League matches. An average of 0.62 goals against per 90 which equates to 24 over the entirety of a Premier League campaign.

In those matches, the champions conceded two or more on just two occasions, despite playing the now infamous high line throughout.

Post-lockdown, as expected, the team took their foot off the gas a little. Mistakes crept into their game and, because of this, it was easier for the opposition to find a way past Alisson.

Instead of acknowledging this as the reason, the finger was pointed at the defensive line and you started to hear people saying things like ‘maybe they need to drop back ten yards’ and ‘it’s been an accident waiting to happen for some time’. You know, reactionary, unfounded statements.

The 2019/20 campaign started off in a similar manner, with the Reds conceding soft goals. Leeds scored three at Anfield and afterwards, talk centred around the defensive line. Liverpool then dealt reasonably well with Chelsea and Arsenal before that game against Aston Villa. People are now looking to rewrite history to suggest the line has been an issue in all four of the games. It hasn’t, not really.

However, Leeds and Villa did have a clear tactic in mind to create favourable scenarios and they executed this plan to perfection.

This is one way to nullify the Liverpool press and exploit their high defensive line. Keep players high and wide, hit long balls to them and have runners from deep. pic.twitter.com/QpLmRoarhH

— Sam McGuire (@SamMcGuire90) October 5, 2020

What both sides looked to do was bypass the midfield but instead of playing the ball directly over the top, they’d play long balls to the wide players and look to isolate Liverpool players in areas they don’t want to be in. Then, with the centre-backs unable to play for the offside, teams would have commit runners from deep to attack the space. And this is why the high line looked so ragged in those games. Villa and Leeds weren’t looking to directly play the first ball into space.

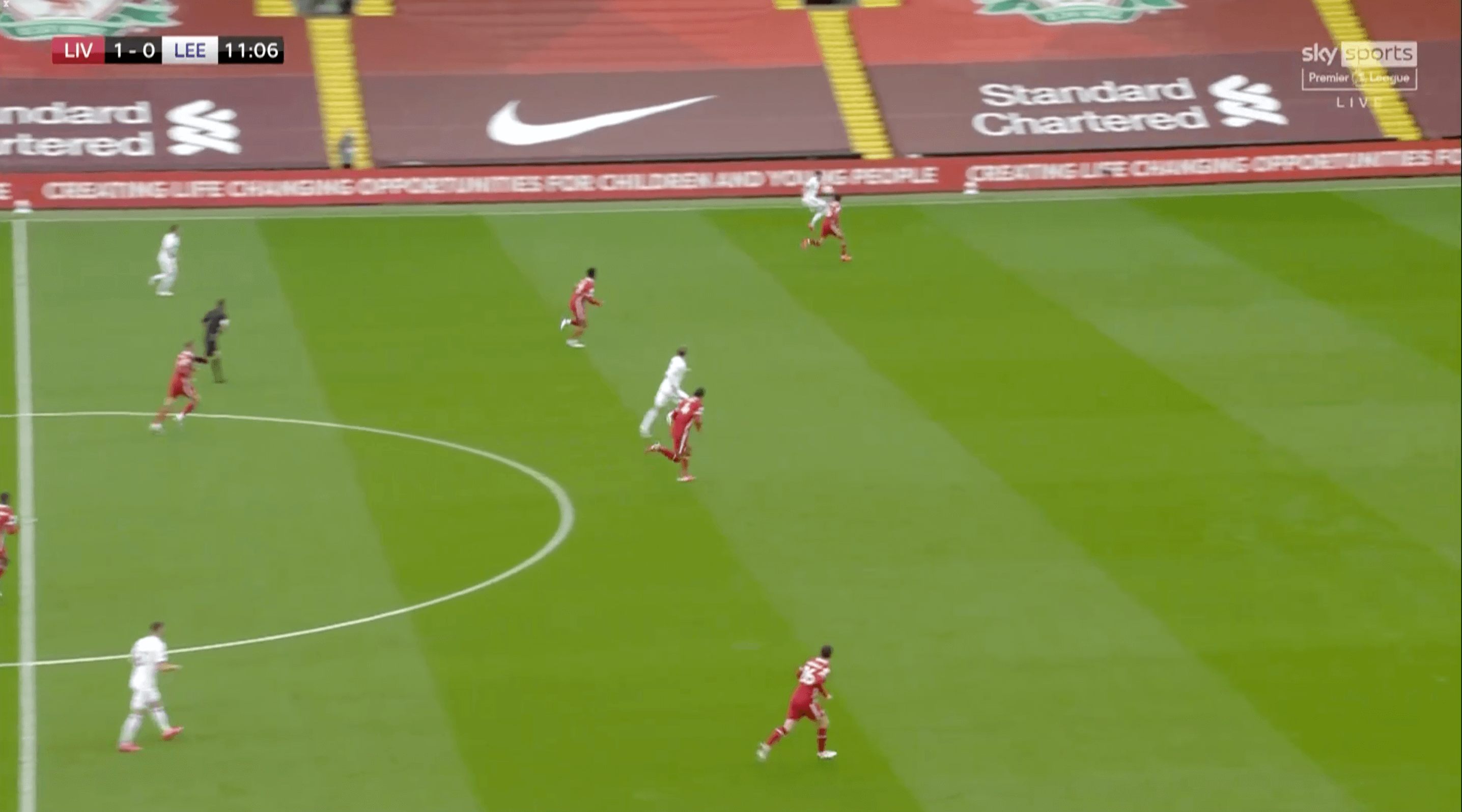

You see it in the still above. Kalvin Phillips, under no pressure, picked out Jack Harrison on Liverpool’s right side. Given he would’ve been onside, Trent Alexander-Arnold has had to track him and this has created the scenario we now see above. Virgil van Dijk is having to sprint back to keep Patrick Bamford from having acres of space to run into unchallenged while Joe Gomez is having to scramble back to cover for Alexander-Arnold.

If Leeds had tried to clip a ball over the top for Bamford to chase, it’s likely Liverpool would’ve been able to catch him offside.

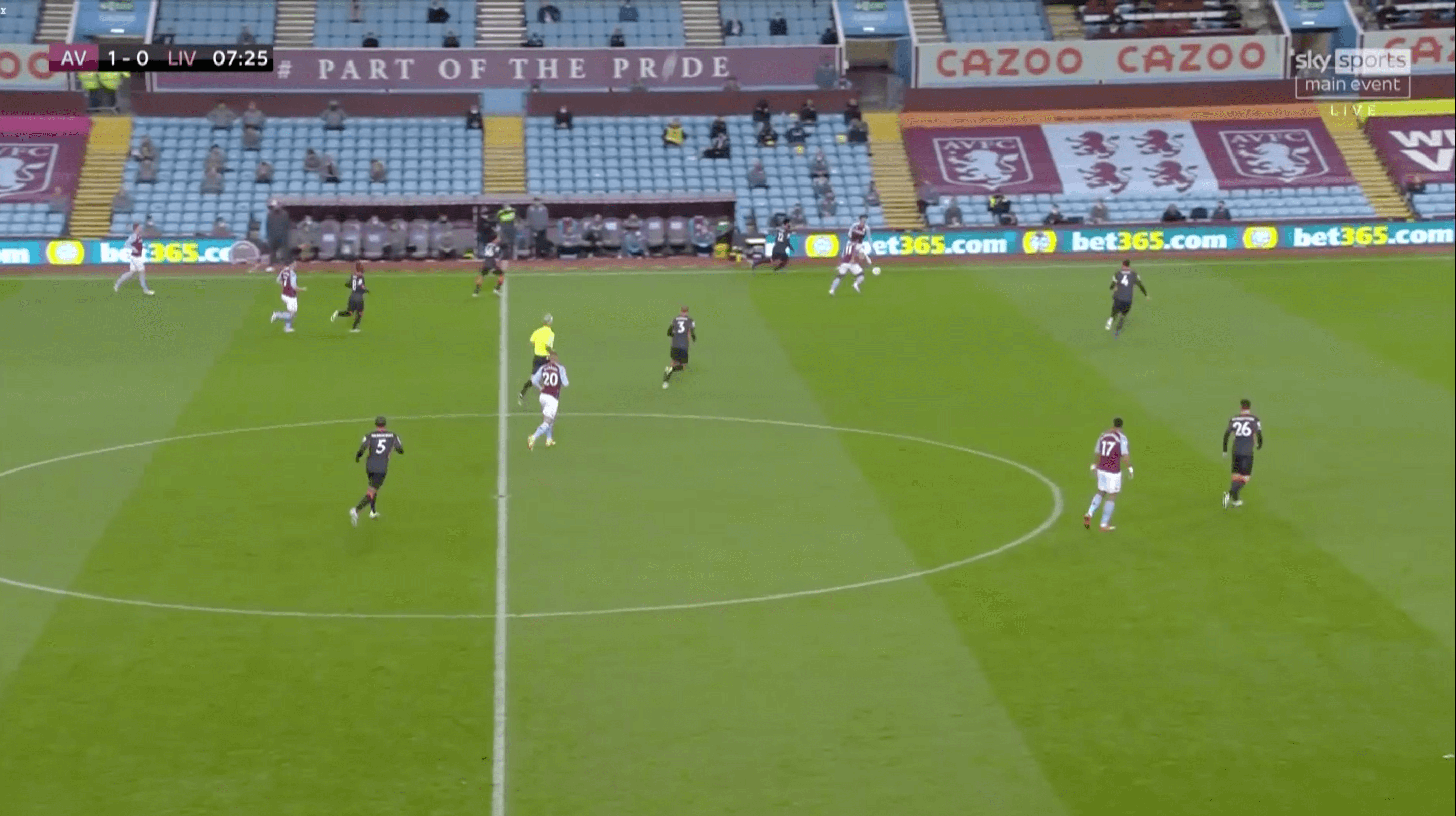

It’s not too dissimilar to what happened against Villa. The hosts doubled up on the Liverpool right and looked to win the second ball off a goal kick. However, Gomez misjudged the flight of it and Grealish was able to bring it down. Van Dijk is forced to cover for his centre-back partner and this creates space in central zones for midfield runners to attack. This had nothing to do with a high defensive line. Villa gambled and had a bit of luck with Gomez missing his header. But it again stemmed from a long ball into a wide area instead of over the top.

Liverpool need to work out a way to ensure their players aren’t isolated in those areas, especially against teams willing to commit men forward. What they don’t have to do is change their entire system. Their high line is one of the reasons they’ve been so successful.